Size matters, part 2

On part 1 we saw how two common std::tuple implementations could result in a sub-optimal layout, and how an optimal layout could be achieved.

Now we'll see what an implementation of a tuple with such an optimal layout actually looks like.

(Note: all this could have benefited from the Boost.MPL library, but I decided not to use it in order to expose more ideas)

Tuples all the way down

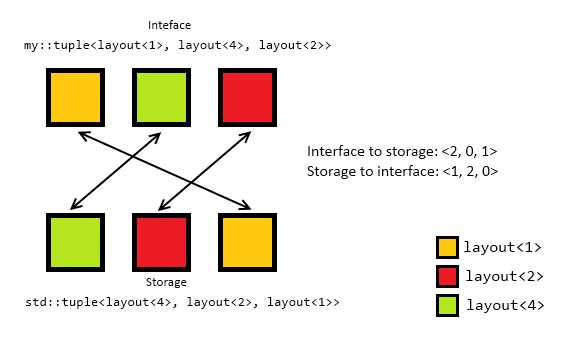

The main difficulty an implementation needs to overcome is the fact that the user needs to treat the tuple as if its elements were in the order of the template arguments: when a call to get<0> with a tuple<int, double> argument is made, the result is the int even if the tuple was reordered to store the double first.

The implementation will need to store the values internally in an optimal order, but map to and from it in the function calls. And how should it store a fixed-size collection of heterogeneous values? std::tuple seems like the most obvious choice. The problem with doing that is that we need knowledge of the implementation: libc++'s tuple lays out the elements in the order of the template arguments, while libstdc++'s tuple lays them out in the reverse order. Other implementations are certainly possible, but I think these two and one with optimal layout are the only sane ones, so we won't catter for other possibilities.

We could implement our own simple tuple for the underlying storage and then we would know for sure what layout it used, but I decided to avoid reinventing that wheel, at least for now.

So, the implementation needs to:

- sort the elements to find out the optimal storage order;

- maintain a map of their position in the template parameter list to their position in storage, so that

std::getworks; - maintain a map of their position in storage to their position in the template parameter list, so that

std::make_tupleworks.

And how should we keep track of these maps? We're going to need some sort of compile-time list. Some template that can have an arbitrary number of parameters, and that has metafunctions to get them by index. Something like... std::tuple! A std::tuple of std::integral_constants works nicely as a compile-time list of integers. Some aliases may make it easier to work with these though.

template <std::size_t I, typename T>

using TupleElement = typename std::tuple_element<I, T>::type;

template <std::size_t I>

using index = std::integral_constant<std::size_t, I>;

template <std::size_t... I>

using indices = std::tuple<index<I>...>;As an example, the mappings for my::tuple<layout<1>, layout<4>, layout<2>>, on libc++'s implementation would be indices<2, 0, 1> and indices<1, 2, 0>.

The sorting of the types

To define the optimal order, we need some metafunction that takes all types involved and produces the two index maps. For ease of communication, let's say we call the maps respectively the optimal map and the optimal reverse map. We need something that looks like this:

template <typename... T>

class optimal_order;

template <typename... T>

using OptimalMap = typename optimal_order<T...>::map;

template <typename... T>

using OptimalReverseMap = typename optimal_order<T...>::reverse_map;How can this be done? Let's start with something simpler: sorting the types by their alignment.

Not all alignments are born equal

Before we go any further, we need look to closer at how we will obtain the alignment of the types involved: there is an easily overlooked issue with references.

alignof(int&) does not give us the alignment that a stored reference (as a member) will have, but instead it gives us the alignment of int. This may be the desirable result in a number of situations, but it is not what we want in this case if we have a tuple with references. We really want the alignment of the reference itself. To retrieve that, we can simulate a member and compute its alignment.

template <typename T>

struct member { T _; };The compiler will always layout member<T> with the proper layout for its member. It could use a stricter alignment than the member needs, but no reasonable implementation will do that. So, if we write alignof(member<int&>) we can grab an alignment value suitable for a reference member.

Carrying all the info

Now that we can compute the proper alignments, we can move on to sorting. The first thing we need is to bundle all the information we need to carry around. Just sorting the types is not enough because we need to know what was their original index.

template <typename T, std::size_t I>

struct indexed {

using type = T;

static constexpr auto index = I;

};For this to work we need a way to make a list of these indexed types from our original list of types. So, let's say that we have an WithIndices alias that produces such a list of indexed types, i.e., WithIndices<std::tuple<int, double, int>> produces std::tuple<indexed<int, 0>, indexed<double, 1>, indexed<int, 2>>. Now we can sort this list.

Sorting with linear complexity

The order of the types will be based on their alignment. One interesting property of those alignments is that they are always powers of two. Not only this means there is a finite and rather small number of possible values, but it also means that we can know them all in advance.

Knowing this means we can write a sorting algorithm that does the sorting with a linear number of template instantiations. That will certainly help with those compilation times.

The algorithm can simply take all the types with each of the possible alignments in the proper order of alignments. The order between types with the same alignment is not relevant. This requires a number of passes equal to the number of possible alignments, and each pass goes through the list once, i.e., is linear.

To iterate over all the possible alignments we can compute the maximum alignment first. That is something that is easily done with a little recursion with an accumulator.

// max<N...> left as an exercise for the reader

template <typename T>

struct alignof_indexed;

template <typename T, std::size_t I>

struct alignof_indexed<indexed<T, I>> : std::alignment_of<member<T>> {};

template <typename T>

struct max_alignment;

template <typename... T>

struct max_alignment<std::tuple<T...>> : max<alignof_indexed<T>::value...> {};Now, we need to iterate over the alignments and sequentially put the types with each alignment on one end of a list. The way we build this list depends on how the standard library tuple we will be using behaves. For this post I will assume an implementation like the one in libstdc++ that lays out the members in reverse order. If we iterate down from the largest alignment, we want to keep putting the types at the start of the list.

template <typename Head, typename Tail>

struct cons;

template <typename Head, typename... Tail>

struct cons<Head, std::tuple<Tail...>>

: identity<std::tuple<Head, Tail...>> {};

template <typename Head, typename Tail>

using Cons = typename cons<Head, Tail>::type;If we were using something like libc++ that lays the members in the same order as given, we could simply switch from prepending to appending.

Next we can build a meta function that appends all types with a given alignment from a given type list into another type list. Nothing harder than the usual recursion over variadic parameter packs.

template <std::size_t Align, typename Acc, typename List>

struct cons_alignment : identity<Acc> {};

template <std::size_t Align, typename Acc, typename Head, typename... Tail>

struct cons_alignment<Align, Acc, std::tuple<Head, Tail...>>

: cons_alignment<

Align,

// append conditionally

Conditional<Bool<alignof_indexed<Head>::value == Align>, Cons<Head, Acc>, Acc>,

std::tuple<Tail...>> {};

template <std::size_t Align, typename Acc, typename List>

using ConsAlignment = typename cons_alignment<Align, Acc, List>::type;And then sorting is simply a matter of iterating over all the alignments, down from the maximum to 0. Since the alignments are powers of two, we just divide by two to go down one alignment.

template <std::size_t Align, typename Acc, typename List>

struct sort_impl

: sort_impl<Align / 2, ConsAlignment<Align, Acc, List>, List> {};

template <typename Acc, typename List>

struct sort_impl<0, Acc, List> : identity<Acc> {};

template <typename List>

struct sort : sort_impl<max_alignment<List>::value, std::tuple<>, List> {};

template <typename List>

using Sort = typename sort<List>::type;Now we can write Sort<WithIndices<List>> and get the optimal layout for a list of types. The next step is to figure out how to build the map and the reversed map from this, which I will explain in the next post on this series.