Size matters, part 1

Variadic templates is one of the interesting new features in C++. It allows one to write generic functions that take any number of arguments of any types. Or class templates like std::tuple, which can have any number of template arguments.

Them tuples

A std::tuple is a fixed-size collection of heterogeneous values. It's like std::pair, but with the number of possible values is not fixed at two. We can use std::tuple for pairs, triples, quadruples, and so on. We can even use it for null tuples (std::tuple<>), or singletons (std::tuple) if the need arises (most likely as the result of meta-programming constructs). These have many uses, but that's not what this article will focus on. This article will focus on the physical layout of tuples, and in two particular implementations of them: the one in libstdc++ and the one in libc++.

Since we're going to deal with layout, it will help to have some way of quickly specifying types with known layout. We can use std::aligned_storage for that, but I'll use an alias for readability.

template <std::size_t Size, std::size_t Align = Size>

using layout = typename std::aligned_storage<Size, Align>::type;Empty types

With that out of the way let us consider the following tuple type:

// a template to make distinct empty types

template <int> struct empty {};

static_assert(std::is_empty<empty<0>>::value, "empty<0> is an empty type");

static_assert(sizeof(empty<0>) > 0, "empty<0> doesn't have zero size");

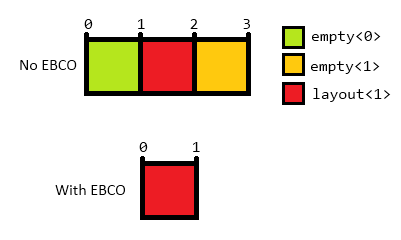

using tuple1 = std::tuple<empty<0>, layout<1>, empty<1>>;How large should this tuple be? The sum of the sizes of its elements is 3. But since two of them are empty types we could optimize their space away: the space they use is just a formality, it is not needed to store anything. This can be achieved through the empty base class optimization (EBCO).

Both libstdc++ and libc++ use EBCO to optimize away empty types in tuples, so the tuple1 above will have size 1 in both implementations.

Padding

Now let us consider another tuple type:

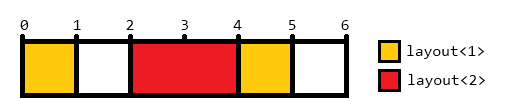

using tuple2 = std::tuple<layout<1>, layout<2>, layout<1>>;What's the size of this tuple? Clearly it can't be less than 1+2+1=4. But it can be more than that. In fact, it will be more than that when using both libstdc++'s and libc++'s implementation of std::tuple, due to the alignment requirements of the types involved.

For now, let's assume we have an implementation that lays out the tuple elements in the order we provided them. That means our tuple will have the following layout:

The second element has alignment two, so it must be placed on an address that is a multiple of two. That means it cannot be placed immediately after the first element, at offset 1, and a byte of padding must be inserted to place it at offset 2. The last element can be placed immediately after that, at offset 4, because its alignment is one.

However, for this to be correct, the whole tuple needs to be placed at an address that is a multiple of two, so that offset 2 within the tuple is still an address that is a multiple of two. For that we need an extra byte of padding at the end.

This makes our tuple use 6 bytes, with only 4 bytes of actual data in it. Can we shave off those 2 padding bytes?

We can, if we change the way we layout the tuple elements. A well-known trick to minimize padding in structures is to place the members with the strictest alignment first. If we do that here, the tuple can be stored using only 4 bytes:

This strategy works because you can always place an object immediately after one with a stricter alignment: a multiple of 2n is a multiple of 2n-1 as well and everything is a multiple of 20 (proof by induction left as an exercise for the reader).

Turns out neither libstdc++ nor libc++ do this kind of optimization. libstdc++ always places the members in reverse order, and libc++ always places the members in the order given. And that's why I set out to write a tuple implementation that uses an optimal layout for storage. But that's a story for another day.